Mgr. Vojtěch Šenkýř

I am a physical therapist and personal trainer. In the hospital and in the gym, I mainly rely on the Kolář DNS technique. I'm currently also learning the Vojta technique.

Other articlesLog in

The negative effects of sitting on back and neck pain and abdominal muscle weakness are well known, and a subject of personal experience for many working-age people. The pelvic floor is an anatomical region that plays an important role in sitting, but is often overlooked in prevention efforts.

Sacroiliac pain, inability to conceive, erectile dysfunction, and painful sex are only some of the symptoms that sitting-related pelvic floor problems may cause. This article takes a systematic look at the pelvic floor and recommends exercises to prevent its dysfunction.

The pelvic floor reminds me a bit of the mysterious Mrs. Colombo, whom everyone's heard about, but no one's ever seen. A lot of people talk about the pelvic floor, but few know what exactly it is. Partly this is an issue of each author using a slightly different definition, but still, let's try to make some sense out of this.

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles and ligaments in the so-called lesser pelvis (pelvis minor), which together form a funnel of sorts and provide mechanical support for surrounding organs.

Krchová (2021) describes the pelvic floor as a hammock hung from the pelvis, stretching between the pubic bone to the tailbone, which consists of three layers and includes the urethral and anal sphincters.

The Latin term for the pelvic floor is diaphragma pelvis, or the pelvic diaphragm. Overall, there are four diaphragms in the body, which are functionally related. The diaphragma oris (the bottom of the oral cavity), the thoracic diaphragm (the “main” diaphragm separating the chest and abdominal cavities, just diaphragma in Latin), the diaphragma pelvis or the pelvic floor, and the diaphragma urogenitale, the urogenital diaphragm, which most authors also consider a part of the pelvic floor, and which plays a part in urination and incontinence.

The pelvis consists of the greater (pelvis major) and lesser (p. minor) pelvis.

The greater pelvis area forms the floor of the abdominal cavity, whereas the lesser pelvis surrounds the cylinder-shaped pelvic cavity.

As we already mentioned, the pelvic floor is part of the lesser pelvis, i.e., the lower portion of the pelvic area, which mostly contains the urinary and sex organs, the rectum, and related veins and nerves. The posterior (back) end of the lesser pelvis consists of the sacrum and tailbone, the lateral (side) limits are the lower parts of the hip bones, and the anterior (front) end are the ischium and the pubis. The perineum forms the bottom. The interior cavity holds the rectum, bladder, and reproductive organs. In women, the dimensions of the lesser pelvis are relevant to childbirth.

The pelvic floor (diaphragma pelvis) consists of two primary muscles - the musculus levator ani (anal levator muscle) and the m. coccygeus (coccygeus muscle).

Most authors also consider the group consisting of the urogenital diaphragm and the sphincters to be part of the pelvic floor.

Many authors further consider the piriformis (m. piriformis) and the obturator internus (m. obturatorius internus) muscles to belong to the pelvic floor as well. These muscles are found in the buttock area and rotate the outside of the thigh bones. Their frequent inclusion in the pelvic floor highlights the functional (and anatomical) proximity of the pelvic floor and the buttocks.

The pelvic floor muscles are supplemented by two fascias, which further support the organs of the lesser pelvis and cover the associated veins and nerves.

The pelvic floor muscles are an integral part of the so-called deep core stabilizing system (DCSS), which stabilizes the spine and maintains intra-abdominal pressure. Other muscles participating in this function are the (thoracic) diaphragm and the abdominal and dorsal muscle groups surrounding the spine. These muscles should co-contract, i.e., function in mutual balance.

An experienced physical therapist can guess at possible pelvic floor dysfunction just by looking – specifically from the aspect of the buttocks.

Poděbradská (2018) writes that the buttocks should be spherical (round).

The symptoms of loose pelvic floor are varied, including urinal and fecal incontinence, descent of lesser pelvis organs, constipation, dyspareunia (painful sex), erectile dysfunction, and pain in the tailbone, pelvis, back, or hip.

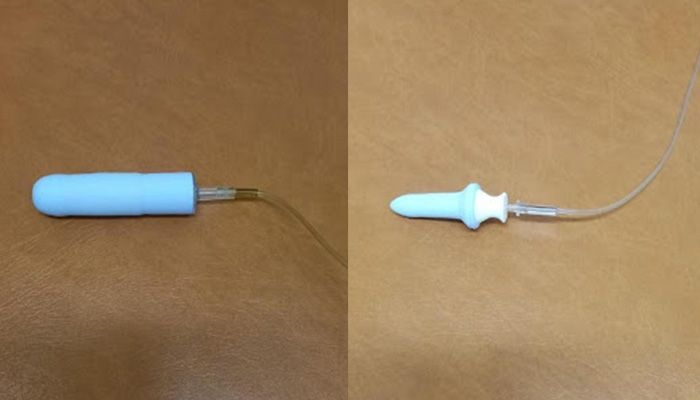

The physical condition of the lesser pelvis is usually examined using the so-called PERFECT scheme. This involves the physical therapist or physician examining (vaginally or rectally) the power (P), endurance (E), repetition performance (R), contraction speed (S), elevation (E), co-contraction with the abdominal muscles (C), and timing of contraction during coughing and against pressure (T).

Before beginning to strengthen the pelvic floor, a thorough examination is necessary.

Now finally, to answer the question of strengthening the pelvic floor. While this is a common patient request, it is not always the right thing to ask. Many patients do not actually need to strengthen the pelvic floor, but to relax it. It is thus best to discuss normalizing tension in the pelvic floor.

The following bullet list summarizes the common therapeutic approaches.

Here are 5 easy exercises that can help women and men prevent pelvic floor disorders. Source: Online video tutorial at Fyziomáma (in Czech).

Wrap the resistance band around your legs above your knees, squat moderately low, then pull moderately hard on band until you feel tension in the buttocks. Hold about 30 seconds.

While lying supine, hold a large exercise ball against a wall with your feet. About a right angle at the knee and hip, abdomen flexed. Alternate pulling one leg and the other off the ball.

Stretch the resistance band between your hands and feet, keep torso flexed, then stretch legs out, and return.

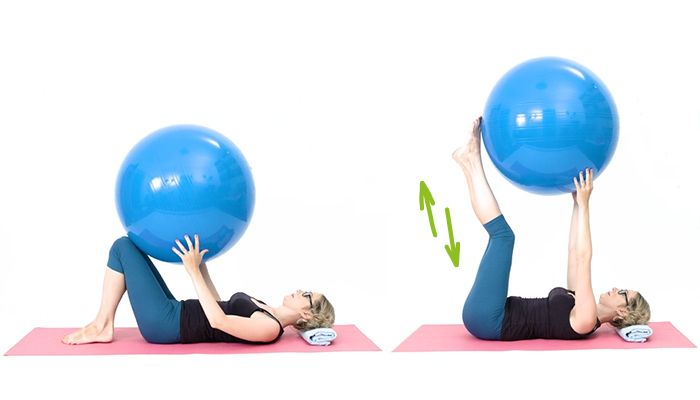

Keeping torso flexed, slowly push exercise ball up your legs while lifting them; then return ball and legs.

Keep about a right angle at the knee and hip, flex torso, then push hands into knees and knees into hands moderately hard. Hold about 10 seconds.

The key to proper seated posture is maintaining a certain degree of motion, allowing the deep core stabilizing system (which also includes the pelvic floor) to remain active. Without good co-contraction between muscles of the abdomen, back, diaphragm, and pelvic floor, the body is left without a large part of its muscular support, which is likely to result in some sort of problem sooner or later.

There are several options for allowing these muscles to stay active while seated. You could use an exercise ball for a backrest, sit on a balance disc, or alternate between sitting on a regular office chair and a gym ball.

An even better solution is available with the Adaptic therapeutic chair, which combines the advantages of the aids discussed above while eliminating their downsides. The tilting seat allows muscles to flex, while the presence of the backrest allows them to relax as well, combining dynamic sitting with the availability of a relaxed position. Adaptic chairs allow the pelvis to move in all directions, allowing the deep core muscles (including the pelvic floor) to remain active, rather than going slack as they do on regular chairs.

Definitely. General well-being and a harmonic domestic environment and sex life can do more for pelvic floor health than the best exercises.

Certainly! Like any other physical activity, jogging improves overall fitness, including of the pelvic floor. Caution is recommended for women after childbirth and in menopause, men after prostate surgery, the overweight, and those with no history of exercise activity. It's best to start with fast walking; you can use Nordic walking poles if you like. Compared to running or jogging, this produces fewer mechanical shocks, which for the untrained can be more trouble than the running is worth.

This is of course a subjective question, but personally I would recommend these 7 rehabilitation experts, all of whom I've had the opportunity to meet in person (ordered alphabetically):

Doctor Skalka (2017) warns that aerobic may affect the pelvic floor negatively in women. Specifically, it is common for aerobic practitioners to fail to properly relax the buttocks and the rectus abdominis (the abs), apply appropriate levels of effort, or properly use the feet while exercising. This leads to young, otherwise perfectly healthy and fit female aerobic practitioners frequently presenting with (paradoxical) incontinence, as well as other pelvic floor symptoms.

I am a physical therapist and personal trainer. In the hospital and in the gym, I mainly rely on the Kolář DNS technique. I'm currently also learning the Vojta technique.

Other articles